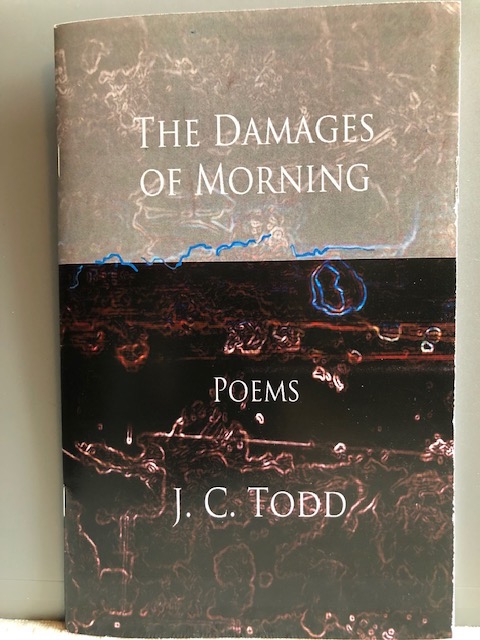

J. C. Todd is author of The Damages of Morning (Moonstone Press), a 2019 Eric Hoffer Award finalist, and What Space This Body (Wind), the chapbooks Nightshade and Entering Pisces (Pine Press) and the collaborative artist books, FUBAR and On Foot / By Hand (Lucia Press). Her poem “Frida” appears in the artist book Mother Monument exhibited at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in DC. Her poems are widely published in such journals as the American Poetry Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, The Paris Review, THRUSH, and Virginia Quarterly Review, and anthologized, most recently in Fire and Rain: Ecopoetry of California and A Constellation of Kisses. Honors include the Rita Dove Poetry Prize and fellowships from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts. She serves as a poet with the Dodge Poetry Program and has been a member of the creative writing faculty of Bryn Mawr College and the MFA Program at Rosemont College.

J. C. Todd is author of The Damages of Morning (Moonstone Press), a 2019 Eric Hoffer Award finalist, and What Space This Body (Wind), the chapbooks Nightshade and Entering Pisces (Pine Press) and the collaborative artist books, FUBAR and On Foot / By Hand (Lucia Press). Her poem “Frida” appears in the artist book Mother Monument exhibited at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in DC. Her poems are widely published in such journals as the American Poetry Review, Beloit Poetry Journal, The Paris Review, THRUSH, and Virginia Quarterly Review, and anthologized, most recently in Fire and Rain: Ecopoetry of California and A Constellation of Kisses. Honors include the Rita Dove Poetry Prize and fellowships from the Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts, and Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts. She serves as a poet with the Dodge Poetry Program and has been a member of the creative writing faculty of Bryn Mawr College and the MFA Program at Rosemont College.

Curtis Smith: Congratulations on The Damages of Morning. There’s a lot of history in these pieces. Have you always had a thing for history, especially this particular, horrible time? If so, what attracts you to it?

J.C. Todd: Thank you, Curtis, for all these questions that go directly to the core of the poems. They’ve sent me back to the origins of this long project in the seeds of poems from travel journals dated eighteen years ago.

I’ve always had a thing for people and their stories. Where they come from, how they got to where they are. The stories that underlie this book led me to historical and cultural museums and documents, to diaries, recollections, histories and fiction and poems and visual art that reveal life during the twentieth century wars in Europe. Many of the poems in this chapbook include bits of stories I’ve heard or read and snatches of visual memory from travels to Central and Eastern Europe

CS: Was the idea for a book dedicated to this time and these themes part of the plan from the beginning, or did you find yourself with a few poems and then discovering a current you wanted to follow? If that’s the case, when did the notion hit?

J.C.T.: I write poems. When recurrent images, themes, or tonalities draw together in a critical mass, I begin to wonder what argument they are making, what dilemma or bewilderment they are investigating, what they are searching for. I have in the back of my mind Denise Levertov’s observation that after gathering poems into her first book, she decided she would no longer write poems but instead write books of poems. I wish I could do that, but my interest and pleasure is in the close work of drafting the poem.

You ask what triggered the impulse toward The Damages of Morning. In 2001, I was invited to Lithuania to be part of Poesijos Pavasaris , the Spring Poetry Festival. That year happened to be the tenth anniversary of the nation’s independence from the Soviet Union. There were readings in Vilnius, the capital, and Kaunas, a major literary center, and then the poets and translators traveled around the country in vans to give readings in former Soviet factory towns, libraries and schools in villages, university courtyards, small cities like Elektrenai. Late one afternoon, leaving the concrete apartment blocks of Elektrenai, we were almost immediately in the countryside—birch and evergreen woodlands interrupted by small farms. At dusk we passed a farmer, yoked to a plow like a beast of burden, cutting a furrow. At the back edge of the field, a thin cow stood by a tilting shed. This glimpse burned into my mind, into my imagination. Although I didn’t realize it until a decade later, it was the image that ignited the poem, “Country Living.” And there was another, equally powerful trigger–the scent of an armful of lilacs given by a trio of women–grandmother, mother, daughter, who had come to a reading in an old Soviet community hall. That aroma led to “Bud.” When I wrote these poems, I didn’t have the sense of a book or a chapbook, but only of writing into a moment.

CS: We’re taken into the horrible tides of war—the confluence of the personal and the innocent against the conflagrations that consume us, a kind of communal madness our kind can’t seem to escape. What drew you to this perspective, especially to the role of the children and other noncombatants?

J.C.T.: Children and ordinary citizens don’t choose war, but in order to stay alive they have to battle the ravages of war. It’s their stories that I’m drawn to. The poems in Damages focus on Central and Eastern Europe during and after World War II. That’s the war I was born into, safe in Brooklyn, NY, but I didn’t realize how war was embedded in me until I traveled to Lithuania and later to Latvia. Since then, I’ve come to believe that throughout our lives, each of us carries the war she/he is born into, spreading its seeds into our own times. Thus the perpetuation of an imagination for war and violence instead of an imagination for peace. During the protests of the sixties, I sang along with Pete Seeger’s “I ain’t gonna study war no more.” Now I think that studying war–how it’s rooted in me and in all of us– is a way to resist the conditions that lead to it.

Poetry has taken me to the Baltics and Germany a number of times. Being in the Baltics, especially, with its vivid reminders of war-time butchery–walls pocked with sprays of bullet holes, the museum of the KGB in Vilnius, the forest at Panerai, which has grown up over the mass graves of tens of thousands of Jews and righteous Gentiles and resisters, being there and hearing the stories brought the lives of the people into me so deeply that I had to share them. The epigraph of the book makes this clear. It’s from Rebecca Seiferle’s translation of Cesar Vallejo’s poem #43 from Trilce: “what escapes into you, don’t hide it. . . .” How do we learn about ordinary people? Through family and neighborhood stories. In this way I have become their family by telling their stories in persona poems and close third-person poems. I wanted them to live in me and in the reader, so we could feel the courage and horror of their dilemmas and their choices. So I wrote as a young teen filled with innocent longing, surrounded by war, struggling for psychological separation from her mother. A pregnant woman, in a village whose gardens and fields have been firebombed, figuring out how to feed herself in order to feed her unborn child. A farmer, who must preserve his starving cow for milk, hooking himself to the plow. And to illuminate the heroism of survivors by counterpoint, two voices are those of their military oppressors, including Josef Mengele. That was a scary point of view, becoming transpersonal with his malign mind.

CS: There is another tide here—the importance of memory—and not in a passive way but as an active pursuit—the responsibility for all of us, the survivors, to remember. Was this theme also in your mind from the start—or did you find it arising as you ventured deeper into the project?

J.C.T.: No one dies in these poems; they live on as survivors rather than as generic victims, as the millions who died. That’s how I want them to be remembered. As I assembled the poems into a chapbook, I thought about how memory becomes a means of transmission from generation to generation, not only through stories but also through cellular and genetic memory and inherited trauma. To answer your question, memory is important to me and so it is woven into the content of many of the poems. As I revised and sequenced the poems into a chapbook, I worked more consciously with the theme of memory, brought it more to the surface.

Aren’t memory and desire at the root of the stories we tell ourselves? Don’t these stories teach us who we are? So maybe the responsibility is to learn the whole story. The story America tells about World War II is a story of heroes. American troops liberated concentration camps; American aid protected the Netherlands from starvation. In the Baltics, I discovered the shadow stories of civilians hanging on to life through bombings and battles and blockades, stories preserved and retold in song, film, photography and family anecdotes. Had my great-grandparents not immigrated from Germany, these could have been my family stories; I might have been born in the midst of the war and grown up in a Displaced Persons camp. So, yes, I did feel a responsibility to listen to the stories and transform them into poems. While the poems are threaded with dire moments, there are brief glimmers of hope–a bulb, a bud, a broth, a box woven from twigs and roots, all of them gathered from tales told by the children and grandchildren of survivors. That’s also part of the responsibility of witness: to affirm that life continues.

CS: I was drawn to the structure of your pieces—they’re so compact and hard-hitting. Can you address the role of structure in your work—how you decide what’s right for a piece?

J.C.T.: The shapes and sonic structures of the poems in The Damages of Morning rose from the voices of the speakers; they reveal character. The almost-bitten-off phrases of a girl on the verge of running away from home. The non-stop litany of things to do of a woman making a family meal from a single spring hare. The syllabically measured voice of a military commander. I think of the poetic line as a visual measure, an emotional measure, an aural measure, an informational measure. Like a many-layered sound byte, it has to be complete unto itself, even as it flows from the line that precedes it and into the one that follows.

There’s a deep pleasure in the discoveries that a structure forces. Sometimes, form is a distraction from the terror of the subject; for instance when drafting and redrafting the poem in Mengele’s voice, I was unnerved that I could even have these thoughts. Form became a personal shield against his misanthropy: I put him in a 7-11: lines of eleven syllables grouped into stanzas of 7 lines. The joke of it kept me writing and kept his voice fresh.

On a deeper level, the essence of these poems and their work is to bring the suffering of the past into the present, to universalize it by making it palpable. I need form as a container and restraint to funnel my own bewildered suffering into the kind of witness that humanizes historical facts and reportage by turning them into story-song. Isn’t the work of poetry, of all art, to transform action and emotion and thought into essence? Aristotle used the ancient Greek term enérgeia, described by British poet Alice Oswald as “something like ‘bright, unbearable reality.’” In the dynamic of “bright” butting up against “unbearable” the energy of the poem is sparked. That’s a joyful moment, fleeting, but real and alive with hope.

CS: What’s next?

J.C.T.: More survivors’ stories. I can’t shake their grip. A new manuscript that’s circulating, titled “Beyond Repair,” follows survivors of wars in the Middle East. Its scope includes civilians, most of them Iraqi and Syrian, and combatants, most of them American. One section of poems, a hybrid sequence of flash-fiction sonnets, are interior monologues of a female Air Force officer, a physician, responding to the daily stresses of her life on a U. S. Air Force Base near Baghdad. She is not a traditional stateside soldier’s wife or a Penelope resisting suitors while her man is off fighting. Instead, the sequence counters the valorization of warrior-hero with the figure of a woman, like Whitman’s wound dresser, working to save lives in the midst of persistent death. Inspired by my daughter-in-law’s tour of duty in Iraq, I read military blogs of personnel stationed in Iraq and Afghanistan to understand the day-to-day lives of the troops and how war zone traumas persisted when they returned home.

I’m also writing poems centered on the life and work of the German Expressionist artist, Käthe Kollwitz (1867-1945), best known for her prints and drawings on the effects of war and oppression on workers’ lives. This is my first fling with intentionally writing a book of poems, although it began with a single poem responding to her etching, Die Pflüger (The Ploughman), whose subject is a pair of boys yoked to a plow. Another man & plow! Sometimes I wonder if a genetic memory of trauma inherited from my German ancestors is guiding me.

https://squareup.com/store/moonstone-arts-center/item/damages-of-morning

https://northofoxford.wordpress.com/2019/04/01/the-damages-of-morning-by-j-c-todd/

Oh! What a brilliant interview! All of J.C.’s articulate scholarship and deep compassion is revealed! You have brought out the power of these poems and gotten to the vast ocean of research and travel surrounding their creation.

Thank you Curtis and thank you J.C. A pleasure and an inspiration to hear (again) this searching engagement with the world. Looking into and writing into those moments, such as the almost unbearably beautiful dusky glimpse outside Electrenai. J.C., you even manage to rescue the phrase “sound byte” for poetry! And yes, our “responsibility is to learn the whole story.” Keep learning, keep teaching, keep writing these stories.